- Hot Summer sale — Get 50% Off — Ends on 31/12/2023

Upcycled fashion show in Ghana offers blueprint for the world

VLISCO UNVEILS NEW COLLECTION

December 12, 2024

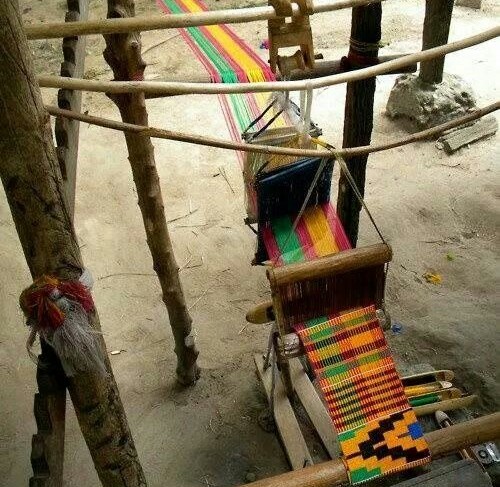

The Fabric of Culture: Ghana’s Kente Cloth Takes Center Stage

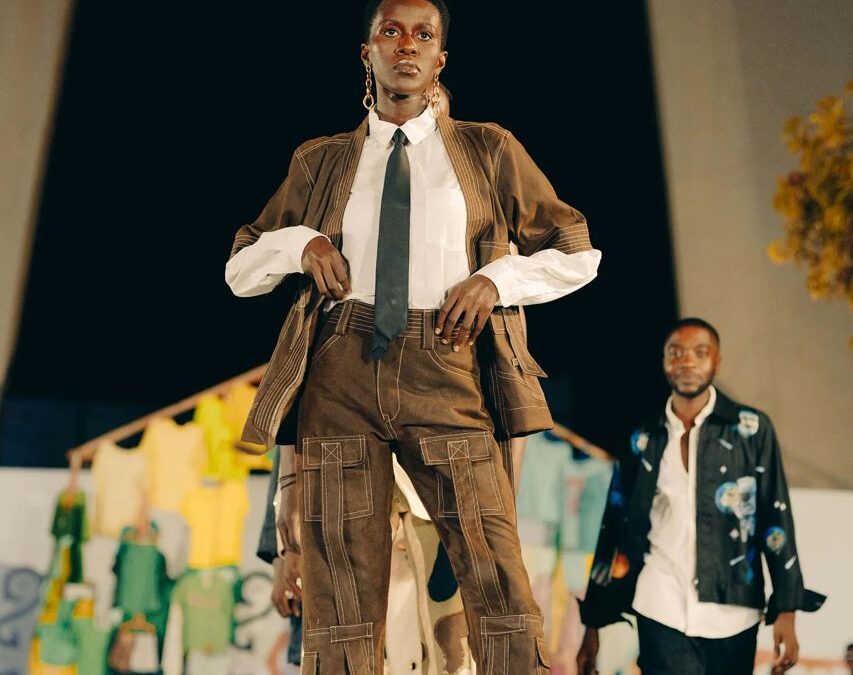

December 13, 2024On a makeshift runway in a public park in downtown Accra on 29 October, models donned looks from five emerging designers that merged traditional artistry with contemporary design using textile waste coming from — or pawned off by — the Global North.

The Obroni Wawu October (OWO) event, which also included thrift vendor pop-ups and DJ sets, shone a spotlight on Ghana’s upcycling ecosystem. The event organisers make clear that while upcycling and sustainability have become trending topics in the fashion industry more broadly, in Ghana they represent long-standing tradition, as well as a lived reality. For them, OWO was part fashion show, part celebration of these principles in practice. It could also serve as a blueprint for fashion weeks elsewhere to follow — if the industry pays attention.

“Ghanaians have always had sentimental value for fashion and textiles,” says Sammy Oteng, senior community engagement manager at non-profit The Or Foundation and lead organiser of the event. “These young designers, the work they are doing, it is not because of what is happening now in the fashion industry or what is trendy. It’s something that has been part of our cultural fabric for the longest time. They are carrying on things that were pioneered by our forefathers or ancestors a very, very long time ago.”

The show featured the collections of five designers — Titus Doku, creative director of emerging brand Calcul; Rebecca Naa Korkor Mensah of Nakoi; Charles Doziah of Xtreet Guidance; Felix Wahab Owusu of OldyBlaq; and Emmanuel Tetteh of Antydote — who sourced their materials from Kantamanto, a sprawling market in Accra. The market has become notorious for the volumes of secondhand clothes that run through it, but it has an important history in the city and in Ghanaians’ lives and has helped to shape the local economy as it stands today. “Kantamanto is an ecosystem. You can buy clothes there, you can get a haircut, you can buy food, you can get your nails done, there’s even a shower space there. There’s so many things you can do at Kantamanto,” says Oteng.

The role Kantamanto plays in people’s lives is at risk of being eroded, though, as the world has — rightly — focused more of its attention on the problems that have arisen from the flood of clothing waste, on one hand, while newer shopping platforms have gained traction on the other. “There’s been an increase in thrifting, but people are not connected to the community that really grounded or started thrifting as we know it now. In the whole of Ghana, Kantamanto is like the one-stop place when you think about secondhand clothing, but because now there’s online shops, people are slowly shifting to those and leaving Kantamanto behind,” says Oteng.

(In a report published last week, Unesco mapped out similar challenges and opportunities facing the African fashion sector more broadly: “Thanks to their unique heritage, unreplicable technical skills and distinctive creative vision, contemporary African fashion designers connect the dots between the past and present,” the report said.)

The work of circularity

On a small scale and within the context of Accra, OWO became a way to showcase and celebrate not only local fashion designers, but the behind-the-scenes work that takes place inside the bustling marketplace of Kantamanto.

Endless streams of secondhand clothing imports arrive at Ghana’s ports weekly. Those need to be transported, broken down, sorted, transported again and probably sorted and transported again before they are market-ready. There’s a lot of manual labour that goes into translating baled-up clothes into organised garment displays that are sorted by category — white T-shirts at one vendor, dress shirts or black pants at another, lingerie or backpacks or sneakers at another — and stacked impeccably for shoppers to browse. It’s the type of work required to make circular fashion a reality, but tends to go unrecognised by many brands talking about circular fashion.

“All of those things are not part of the daily conversation in Kantamanto — it’s there in practice and in reality, but it’s not spoken. It’s like the flip side of what happens in the Global North, where all the words are spoken and all the ideas are intellectually there and true, but then the reality or the manifestation of the ideas is not really there,” says Liz Ricketts, co-founder of The Or Foundation. “Designers make headlines because they upcycled a couple things or they have a pilot collection, but here in Kantamanto it’s just part of the norm. Everyone is upcycling. They don’t try to make it more than what it is.”

That’s where OWO offers potential to be a model for other fashion shows to borrow from: it centres upcycled, zero-waste looks on the runway, but it was also organised and produced in close collaboration with the communities it represents, rather than on behalf of them. The goal, in both its outward presentation and its behind-the-scenes execution, was to elevate the local fashion scene from within — spotlighting local, emerging designers, while also highlighting the layers of people who contribute to those designers’ ability to envision and then manufacture the collections they send down the runway.

For Ricketts, it’s almost an embodiment of the old adage, “show, don’t tell”: “For me, OWO represents that alternative world where it’s not just rhetoric, but where sustainability is truly a culture,” she says. She expanded in an Instagram post this week: “We often say that sustainability is a language. A language can be lost in one generation and the Global North has essentially lost, or forgotten, this language — people wear garments only a handful of times and donate their clothes because they don’t know how to sew a button back on their shirt,” she wrote. “Perhaps even more important than centering upcycling, OWO is a model for how fashion can de-Centre everything that is not sustainable. Because more than what was said or explained, the value of OWO is really in what can go unsaid because it is felt.